Reflections on a decade in Peru

Peru seems to have turned down a dead-end alley. "The Crisis," a cancerous malaise that has spread through the national social fabric, is calling into question the continuance of fundamental institutions. Fettered by external and internal handicaps, the country's leadership seems incapable of responding to the challenge. "The Crisis" is no longer a temporary obstacle to be surmounted or simply a question of rounding up the hard dollars to pay off the Manhattan bankers, but a chronic decaying of the country's self-image and its means of regenerating itself.

There are five features that distinguish Peru's current predicament:

As with the bloody events this past year, like the "El Sexto" prison mutiny ![]() or a Sendero blackout, Peruvians are aggressively confronted with the full impact of "The Crisis." What we are witnessing is the breakdown of a "world view" (Weltanschauung) that has structured the perceptions of Peru for decades: Peru has tried to move towards capitalist modernization, compressing 400 years of Western civilization and development into a couple of generations, a blind leap from feudal exploitation to the American way of life.

or a Sendero blackout, Peruvians are aggressively confronted with the full impact of "The Crisis." What we are witnessing is the breakdown of a "world view" (Weltanschauung) that has structured the perceptions of Peru for decades: Peru has tried to move towards capitalist modernization, compressing 400 years of Western civilization and development into a couple of generations, a blind leap from feudal exploitation to the American way of life.

I eventually left Peru in November 1990, only to return in 1993-95.

On February 22, 1973, I stepped off an airplane at Jorge Chavez International Airport![]() and into life in Peru. I took the drive past the shantytowns that had only just occupied the desert wasteland. Although they frustrate the tourist agencies' desire to cast Peru as a lyrically picturesque postcard, the physical transformation of these settlements over the past decade, from reed mats and scrap wood to brick and mortar, demonstrated how the working class fulfilled its aspirations, though not all of them.

and into life in Peru. I took the drive past the shantytowns that had only just occupied the desert wasteland. Although they frustrate the tourist agencies' desire to cast Peru as a lyrically picturesque postcard, the physical transformation of these settlements over the past decade, from reed mats and scrap wood to brick and mortar, demonstrated how the working class fulfilled its aspirations, though not all of them.

Up to the late 1970s, the urban working class has been carried on the "development" wave. Over the pumps and dips in the economy, the material progress dripped down to the bottom. Accepting the "official" vision of progress, provincial migrants flocked to Lima and other cities seeking a better life. If the government could not put public services in Cajatambo and Cora Cora ![]() , the provincial masses came to the services. Access to a piece of sandy wasteland provided a savings deposit in bricks, potential workplace, nearness to entertainment, social services and advanced education for children, and eventually a decent retirement and secure setting for the extended family. Better education, the communication media and other market forces were creating a growing, but incipient awareness of what human dignity really means -- and also raised consumer expectations. But it was a jerry-rigged system and the accumulating forces were also making more of Peru vulnerable to the troubles to come.

, the provincial masses came to the services. Access to a piece of sandy wasteland provided a savings deposit in bricks, potential workplace, nearness to entertainment, social services and advanced education for children, and eventually a decent retirement and secure setting for the extended family. Better education, the communication media and other market forces were creating a growing, but incipient awareness of what human dignity really means -- and also raised consumer expectations. But it was a jerry-rigged system and the accumulating forces were also making more of Peru vulnerable to the troubles to come.

The squatters at the Asentamiento Humano Victor Raul Haya de la Torre![]() in Independencia

in Independencia ![]() are late-covers in the grab for prosperity, having occupied an abandoned factory on Christmas Eve, 1978. Within a large, walled compound, divided neatly into "cell blocks," 3,000 families eel out an existence on odd jobs and hand-outs. Even their presence on the land is precarious because they have no legal title to the terrain. Like the prisoners at "El Sexto," they are awaiting a verdict on their lives. They are trapped in a blind alley.

are late-covers in the grab for prosperity, having occupied an abandoned factory on Christmas Eve, 1978. Within a large, walled compound, divided neatly into "cell blocks," 3,000 families eel out an existence on odd jobs and hand-outs. Even their presence on the land is precarious because they have no legal title to the terrain. Like the prisoners at "El Sexto," they are awaiting a verdict on their lives. They are trapped in a blind alley.

|

A team of psychotherapists, headed by Cesar Rodriguez Rabanal, has found that much of the frustration and hostility that the residents feel is vented against themselves (alcoholism), their families (abused and abandoned dependents) and neighbors (feuding), instead of working towards a shared objective. Survival instincts reign supreme, to the point that children are frequently given away to strangers and the younger ones are literally the wimps of the litter at mealtime. In this culture of poverty, the possibilities of pulling oneself up by the bootstraps are remote, and there are other factors that subvert even the most elementary efforts.

"It is not a human space propitious for generating human values," says Rodriguez. "Something like generosity is a luxury here."

This invasion, near the bottom of Peru's social pyramid is a compressed version of what "The Crisis" is doing throughout the rest of the society. Some of the most traumatic experiences are faced by middle-class families who suddenly realize their well-being is precarious, at best, as when a child comes down with tuberculosis, a socially stigmatized illness in Peru. The Central Morgue in Lima today processes more suicides, a middle-class phenomenon, than murders for the first time in its history.

"There are a whole set of social and psychological problems that have lain latent for decades and are now detonated by the fuse of the crisis," says psychologist Elvira Soto of the Centro de Evaluacion, Diagnostica y Asesoramiento Psico-pedagogico (CEDAP)![]() .

.

Sometime in 1974, Peru crossed an invisible line. Conservative critics are correct that the military regime must carry a special burden of guilt for failing to see the financial and economic storm clouds just over the horizon. But it was a blindness that was shared by almost all Peruvians. What looked then to be a momentary sputtering of the economic motor with the first price hikes of the OPEC oil cartel, turned into a "chronic" crisis cited by each new finance minister as the source of failure. In 1984, Peru has struggled to maintain the same living standards as those in 1966. ![]()

This violent rupture has rocked a fundamental idea that powered the government and other decision-makers in the post-World War II period: progress as a quasi-vegetative growth, whose "profit" can be recycled back into the productive system or redistributed among the less-wealthy. More exports, imports, machinery and technology would naturally translate into improved living conditions for the majority of Peruvians. Now it is no longer a question of how to administer and distribute this "surplus wealth" but how to ration out the impoverishment.

Peru is quickly reaching the critical point where the built-up social demands, the "structural violence" as social scientists like to call it, will start to take a dramatic toll on the nation. It does not matter whether Peruvian opt for Sendero Luminoso's primitive vengeance or for stoic acceptance of their plight, the results will be equally decimating.

The psychiatrist Max Hernandez ![]() says, "Peru will emerge from this process changed. I only hope that I will be able to recognize myself in its image."

says, "Peru will emerge from this process changed. I only hope that I will be able to recognize myself in its image."

In response to both circumstances and design, the State has had to reduce its capacity to influence events affirmatively. The government is becoming passive and atrophied, cutting back on salaries, expenditures and initiative. Over the past two years, the government has been reduced primarily to defending the "foreign front," maintaining Peru's financial standing. In the future, its increasingly heavy task will be to keep the streets safe -- a cop or trooper on every corner and power pylon -- to defend in the most repressive terms against crime and subversion. Under this uncommon pressure, it is only natural that the State save its reserves for a last-ditch defense of national interests, resources and institutions, but this shrinkage has not been carried out rationally and with clear priorities. What is worse, the government has become the "first predator of the country's capital," says a construction contractor. "It violates a long chain of moral and ethical commitments."

With the State's withdrawal, the "informal" world has gained more terrain in the society spontaneously. While the underground economy has become the theme in vogue to explain the crisis of legitimate industry and commerce, other ramifications are also surfacing: as the sociologist Jose Matos Mar ![]() likes to list with a naturalist's delight -- contraband, chicha music

likes to list with a naturalist's delight -- contraband, chicha music ![]() , coliseos

, coliseos ![]() , petty corruption, pre-university "academies," crime, sweatshops, Sendero, drug trafficking, parallel markets and the non-capitalist concept of reciprocity among campesinos, both good and bad, outside the law and on the borderline. In varying degrees, the state apparatus and the establishment have had to tolerate and accommodate the "informal" world because the "underground" provides a range of survival tactics that allow the legitimate superstructure to remain intact.

, petty corruption, pre-university "academies," crime, sweatshops, Sendero, drug trafficking, parallel markets and the non-capitalist concept of reciprocity among campesinos, both good and bad, outside the law and on the borderline. In varying degrees, the state apparatus and the establishment have had to tolerate and accommodate the "informal" world because the "underground" provides a range of survival tactics that allow the legitimate superstructure to remain intact.

|

Underground economy expert Hernando de Soto ![]() , who feels like a creole Adam Smith discovering a new invisible hand, has pointed out that this "informal world" has always existed in Peru, but has surged to the surface in the current crisis. The Peruvian system has historically been a tightly knit club of entrenched interests (not necessarily a Club Nacional

, who feels like a creole Adam Smith discovering a new invisible hand, has pointed out that this "informal world" has always existed in Peru, but has surged to the surface in the current crisis. The Peruvian system has historically been a tightly knit club of entrenched interests (not necessarily a Club Nacional ![]() conspiracy because it includes a "privileged" middle class), offering only limited access for upward mobility and assimilation.

conspiracy because it includes a "privileged" middle class), offering only limited access for upward mobility and assimilation.

The political forces that aspire to power have been bewitched by the illusion of the "Assault of the State" -- once in control, then the country can be controlled by pulling strings and issuing decrees. Economic interests repeat the formula by trying to win privileges through access to government. A special law or regulation in a businessman's favor was better than a patented process for making a profit. But the system is turning against those in power.

The military-enforced reform of the 1970s was a scribe's game, a deluge of supreme decrees and regulations that attempted to rearrange the system. The legal devices to guarantee the "fairness" of the system turned into economic bottlenecks. But to blame this tendency exclusively on the military is inaccurate. Many of these provisions were begun decades ago, and the controlist bureaucratic core of Peruvian government goes back to Colonial and Inca periods.

The Accion Popular-Partido Popular Cristiano ![]() partnership tried to stage a counter-reform by issuing its own landslide of extraordinary degrees and regulations -- Congress has proven inefficient in taking on this task - to wipe out laws that prevented market forces from functioning smoothly.

partnership tried to stage a counter-reform by issuing its own landslide of extraordinary degrees and regulations -- Congress has proven inefficient in taking on this task - to wipe out laws that prevented market forces from functioning smoothly.

Perhaps, this vision of an "official" Peru is best personified by President Fernando Belaunde himself. In the past general elections, Belaunde represented the desire of the majority of Peruvians to return to an idealized "pre-Revolutionary" world, an antediluvian time when affairs were not complicated by the impression of the impending collapse of a social order, a regression to a childlike simplicity (summarized in the campaign slogan "Work and let work"). Belaunde's architectural outlook -- decorous housing projects, spectacular feats of engineering in the Andes, superhighways to nowhere -- require the pouring of cement into the mold of an idealized Peru to somehow harden the dreams and aspirations into reality. This perspective implied the building of a physical framework for a visionary 21st century, and also made enormous leaps over the immediate needs of the country. Belaunde's penchant for protocol, formalism and constitutional order disguises the harsh contradictions of the system that still fails to represent the people's interests.

|

Belaunde, large sectors of the establishment, and vast sectors of the public have blocked out much of what is happening in the country. It is a trait that borders on repression in the psychoanalytical sense. In response to the threat from Sendero Luminoso, Belaunde has tried to point a finger at "foreign" elements -- drug mafia, imported marxism, activist priests and international research grants -- but there was nothing intrinsically wrong with the country that a little hard work would not fix.

In this context, the approval of the IMF and international banking community takes on a psychological importance when the legitimacy of the government is challenged by the rising tide of opposition: if the internal rules of the game go against the government, it is reassuring to latch onto the universality of international by-laws to justify a regime. But the Latin American debt crisis has another reading. Peru's elite has been betrayed by its own model of behavior -- the developed countries and the international economic system. The IMF's demands taken to the bitter extreme would mean putting through the meat grinder much of Peru's industry, commerce and "Miami Triangle" -- the residential ghetto that stretches from the patrician mansions of San Isidro to the sunny refuges of La Molina and back to the nostalgic cliffs of Barranco. Indeed, increasing numbers of the establishment will probably drop out completely, packing their bags for the US and Europe.

With an ironic twist, one of Belaunde's self-proclaimed achievements, the re-establishment of full press freedom, has turned against him. The contrasts between the versions of newspapers like El Comercio ![]() and La Republica

and La Republica![]() , and between TV news programs like 24 Horas

, and between TV news programs like 24 Horas ![]() and Vision/90 Segundos

and Vision/90 Segundos![]() drive home how distant the official vision of Peru is from reality. It also shows that although many participants in this fresh dip into the harsh terms of daily life can describe events, few are capable of placing it in context, explaining it and pointing toward a solution. Thus, the purple prose coverage of events like "El Sexto" prison mutiny and Sendero subversion.

drive home how distant the official vision of Peru is from reality. It also shows that although many participants in this fresh dip into the harsh terms of daily life can describe events, few are capable of placing it in context, explaining it and pointing toward a solution. Thus, the purple prose coverage of events like "El Sexto" prison mutiny and Sendero subversion.

After raising hopes during the first two years of their government, Alán García and APRA literally dismantled the government and left it in a shambles.

APRA ![]() is grooming itself for office in 1985, thanks to a thorough face-lifting under presidential candidate Alan Garcia and the AP-PPC fumblings in running the country. But it shares the same "world view" as its predecessors and believes firmly that changing a few laws and pulling a few strings will right the system. Although García currently seems to be enamored with the image polishing needed to be elected, he has already broken many of the molds of APRA's 50-year history and has gone out of his way to seek out contacts with sources that lie outside the "official" vision.

is grooming itself for office in 1985, thanks to a thorough face-lifting under presidential candidate Alan Garcia and the AP-PPC fumblings in running the country. But it shares the same "world view" as its predecessors and believes firmly that changing a few laws and pulling a few strings will right the system. Although García currently seems to be enamored with the image polishing needed to be elected, he has already broken many of the molds of APRA's 50-year history and has gone out of his way to seek out contacts with sources that lie outside the "official" vision.

Izquierda Unida![]() , in spite of itself, has been one of the few political forces that experiments with the alchemy of Peru's underground ingredients. Alfonso Barrantes's performance in last November's municipal elections gave him the Lima provincial mayoralty, but it may not prove to be a permanent bond between the radical left and the working classes.

, in spite of itself, has been one of the few political forces that experiments with the alchemy of Peru's underground ingredients. Alfonso Barrantes's performance in last November's municipal elections gave him the Lima provincial mayoralty, but it may not prove to be a permanent bond between the radical left and the working classes.

The Peruvian left hit its highwater mark in 1985 and seemed on the verge of becoming the main opposition force, but it imploded under the pressure of Sendero's insurgency and its own contradictions by 1990.

The Peruvian left came of age outside the legal apparatus during the military revolution. Although right wing observers attribute the left's growth to the military's radical rhetoric, the left's growth is largely the result of a political praxis that relied heavily on marginal and informal social forces, working outside the legal apparatus. The unions, campesino and shantytown organizations, clandestine meetings, regional fronts and universities (a marginalized institution because it is dedicated to the critical study of reality) all provide arenas for grassroots political activity. Although some left wing activists joined the Velasco regime, the parties that grew were political outsiders. The strongest leftist voting block did not have a party militancy, but were independents who had a gut feeling that something is out of kilter in the country.

The central problem for Izquierda Unida has been the internal contradictions of the left, the lack of organization, inconsistent leadership and an almost sadistic pleasure at seeing the system go down the tubes. The left also represents vested interests, like trade unions, the party bosses and personal ambitions, that have a stake in the establishment.

We can now see that Alberto Fujimori, an Asiatic despot transplanted to the Andes, was the instrument for restoring a harsh discipline on the society.

The often repeated convocation to draft a "national project," first heard in the Constituent Assembly![]() , is a need to try to forge some kind of unity out of the debris. But the problem is that a purely intellectual exercise soon mixes wishes with reality, a clash between the vested interests of the present, concerned primarily with conserving their good fortune, with the outsiders, the alienated and the tremendous social demands of providing a minimum of social services for 19 million Peruvians

, is a need to try to forge some kind of unity out of the debris. But the problem is that a purely intellectual exercise soon mixes wishes with reality, a clash between the vested interests of the present, concerned primarily with conserving their good fortune, with the outsiders, the alienated and the tremendous social demands of providing a minimum of social services for 19 million Peruvians ![]() . "The only thing holding this country is that tenuous glue called democracy," says a troubled executive. But Peru's hand-cuffed democracy cannot adequately absorb the impulse of millions of disenfranchised Peruvians.

. "The only thing holding this country is that tenuous glue called democracy," says a troubled executive. But Peru's hand-cuffed democracy cannot adequately absorb the impulse of millions of disenfranchised Peruvians.

|

Peru will emerge from this dramatic period profoundly altered, just as the Depression and World War II marked several generations of Americans and Europeans, at least the survivors. Hopefully, Peruvians will know how to use "The Crisis" as a spur to tackle many of the bottlenecks impeding a realization of Peru's full potential.

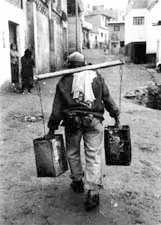

A vital question, yet unanswered, is what is holding Peru together during these bleak times. From Moyabamba![]() to Taquile Island

to Taquile Island![]() , from Pamplona Alta

, from Pamplona Alta![]() to Pucallpa

to Pucallpa![]() , there is a partially tapped resourcefulness that keeps people alive and kicking. When Peru's leaders stop trying to patch up the system and look for longer-term solutions, they will find that the bedrock of a new country can be found already in place.

, there is a partially tapped resourcefulness that keeps people alive and kicking. When Peru's leaders stop trying to patch up the system and look for longer-term solutions, they will find that the bedrock of a new country can be found already in place.