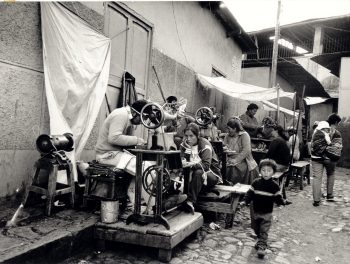

On the rocky, steep slopes of the Cerro San Cristobal, know as "the Hill" to its residents, shoemaker Francisco de la Cruz has identified a snag in his on-man production line: he needs to get his hands on a sewing machine.

The conclusion may seem simple, but for de la Cruz it is a big step beyond day-to-day survival. Since setting up his home workshop eight years ago, de la Cruz, 43, and his family of nine have stood literally in danger of eating up his working capital.

|

Over the past decade, Peru's underground economy has exploded as the legitimate economy's growth was stunted by bureaucratic mismanagement, foreign debt restrictions and recessive economic policies. According to government figures, a third of Peru's urban work force has joined the underground economy as street venderos, small producers and odd jobbers.

Hernando de Soto of Liberty and Democracy Institute estimates that more than a third of Peru's gross domestic product is linked to what is euphemistically called the "informal sector."

Many microbusinessmen are mining market niches which are not met by mainstream companies. For instance, de la Cruz sells sturdy, far-from-stylish shoes to provincial markets as far away as Cusco and Arequipa in the south. Others form a vast network of retailers in Lima's shantytowns. What unites them is that they operate outside the law, a permanent moonlighting in broad daylight.

For thousands of workers, the informal economy offers a last resort for employment. Many legitimate companies use the informal economy as an under-the-counter sales outlet or supplier.

The government of President Alan Garcia has decided to try to fit the underground economy into its unorthodox economic program. The Institute for the Development of the Informal Sector (IDESI), a non-profit organization sponsored by the Peruvian government, international development agencies and private enterprise, is making bootstrap credits available to turn tiny businesses into viable enterprises.

In June, last year, de la Cruz and five other shoemakers who live on the Hill formed a "solidarity grou" and signed a contract with the local IDESI office, which guarantees loands for working captial. Should any member of the group be unable to make his monthly payment, the other members must make up the difference. "In absence of capital guarantees, we're giving loans on their work" said Susana Pinillas, executive director of the IDESI program.

In its first year of operations, the program has reached more than 15,000 microbusinesses, awarding about $3 million in loans, making it the fastest-growing program of its kind in the world, international labor consultants say. Having passed the teething phase, it is now setting the ambitious goal of finding 90,000 fresh clients this year.

The loans start out at as little as $35 per person and rise to as much as $300. The standard commercail rate of 4 percent per month is charged.

The system, in which IDESI guarantees lending agencies, credit unions and commercial banks 60 percent of the loan captial, has worked so well that delays in payment have been practically zero, far above the average for the regular banking system, and there has been no default yet, program officials say. These results have attracted the Banco de Credito, the largest commercial bank in Peru, which is putting up its own funds. The bank's management wants to move aggressively into this line of business for up to 145 percent of its loan portfolio, about $60 million. "This is just an extension of our personal banking service," said a bank executive.

"For this program to have long-term success, it has to link up with the comemrcial banking system," said William Tucker, an International Labor Organization consultant. Eventually the IDESI program wants to nurse the microbusinesses into a permanent relationship with the banking system by allowing them to demonstrate their credit-worthiness.

However, the idiosyncrasies of the underground economy mean that the banks and borrowers must learn to adapt to each other. Just entering a bank can be culturally intimidating for many small businessmen, some of who are barely literate.

This month, de la Cruz and his associates paid back puntually a special "pre-investment" loan of $800 each. They are the first participants in the new aggressive stage of the bootstrap program to allow microbusinesses to make a technological step forward. With training courses, technical assistance and some brainstorming behind them, they realized that with just one sewing machine among them, they cannot keep up with the deman. By adding a couple of machines and other equipmenet, they can specialize in the production process, increase their output and diversify their products.

Amid the painted graffit calling for armed revolution that covers the walls of the Hill, de la Cruz said optimistically, "We've just begun to resolve our problems."

IDESI expects to authorize loans of about $2,000 per new job position in this phase. Studies show that an average microbusiness has an average capital of $500 per work position. In the modern economic sector, it takes an average investment of $13,000, according to independent studies, though more advanced manufacturing plants can require up to $40,000 per work position.

In the next five years, the labor market will be swamped by another 1.2 million job seekers. That means that if Peru's traditional business sector carried the load, a minimum $15 billion would have to be invested, close to what Peru's gross domestic product is today. Government economic strategists are hoping that microbusinessmen of the underground economy can provide a cheap, entry-level job market, as well as a healthy boost to private enterprise and income distribution.