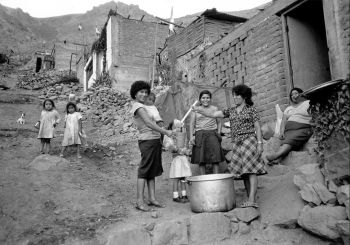

Lunch pails in hand, a line of women, children and elderly men chat on a dirt-floored back patio equipped with steaming kerosene stoves, work tables and benches. They glance at the bulletin board for the news, exchange the latest gossip or talk about the problems of Comas, a dirt-and-brick working-class neighborhood which terraces its way up a mountain slope on the northern outskirts of Lima. Cooks are distributing the day's lunch of soup and a tick stew.

|

For 50 families, this scene is repeated twice daily at the "union" family kitchen. Each family shares responsibility for preparing a breakfast of hot cereal and a hot lunch. At 15 cents, the main meal is the best buy in town, but for the participants it takes the bite out of hunger.

The union kitchen is the matriarch of a growing grassroots movement. Five years ago, several mothers got together to stretch their food. Today more than 400 family kitchens are following their example, feeding an estimated 10,000 families in Lima's most impoverished districts.

"The kitchens are spreading like wildfire," sociologist Violeta Sara-Lafose said.

Peru is struggling through the worst recession of the century. In shantytowns, meals of tea and bread are common, and an inadequate diet is creeping into the middle class. A pediatrician at Lima's only children's hospital said four patients in five suffer from malnutrition.

But the kitchen movement is yielding other dividends by giving women a new self-esteem and awareness in a society dominated by Latin machismo. Social workers say that kitchens constitute the largest women's rights organization in Peru, though its first concern is filling children's stomachs.

"We're learning that we can get by on out own," says Aide Massone, an energetic black grandmother and co-founder of the union kitchen. "We no longer have to hold out our hands for help all the time."

The first triumph for the women was getting out of their own solitary kitchens. Daily meal preparation at home, including outings to market, takes as long as eight hours, while the union kitchens take only one day a week on average, and with the free time the women can become their family's second wage-earner. A recent survey showed that two-thirds of the participating women earn extra income from cottage industries such as washing clothes, street vending or working in Lima's sweatshops.

"When we were isolated in out homes, problems seemed insurmountable," said Cirila Palomino, a leader of the Comas women's federation. "But side by side here in the kitchen, they are cut down to size."

Just joining a family kitchen can be a major achievement, and many of the women said they will not leave even if their economic conditions improve.

Hard up as they are, kitchens help out those who are worse off. When a wage-earner loses a job, a major illness hits a household or a husband abandons his wife, a kitchen can issue free rations for a while.

Feeling their male pride as breadwinners bruised, husbands have been known to throw the food back in their faces.

"But when a husband loses a job and the family kitchen gives help, his attitude starts to change," says Ms Sara-Lafose, who has been studying the kitchen phenomena for the past year.

The kitchens have also met resistance on other fronts. The police have harassed them for being "terrorists" because of their mysterious meetings -- at which they plan menus. Political parties have alternately courted them and tried to manipulate them as a potentially powerful political force. At a recent convention of shantytown organizations, the predominantly male leadership relegated the kitchen federation to the status of "fraternal observers" rather than giving them voting rights.

"The traditional male leaders are wary of the kitchen federations because they don't know how to control them," said an organizer.

Spurred by the economic crisis, representatives of more than 100 kitchens met this year for the first time in a city-wide conference to share recipes, experience and concerns. A co-ordinating committee was set up, and the organization has started to edit a magazine and bulletins, to stage marches against cost-of-living increases and to negotiate with municipal authorities for better public services. It has also got in touch with other cities and consumer organizations in other countries.

Peru's communal kitchens have their roots in the Andean heritage of most of the participants, three-quarters of whom are migrants from the Sierra, where communal lifestyles have survived for centuries.

The success of the movement, which is self-sustained aside from some food donated by church charities, has finally started to attract the Government's attention. Officials admit that attempts to improve nutritional standards have been ponderous and underfinanced.

First Lady Violeta Correa de Belaunde has set up a program to provide building material, stoves, cooking equipment and some food stables for more than 100 kitchens of community organizations. The central bank has given her agency a $1-million grant to get the program into full swing.

The leftist municipal government of Lima is carrying out a pilot project, supplying weekly provisions to kitchens on credit and at wholesale prices. Almost all the family kitchens make daily purchases at neighborhood markets. An even more ambitious idea is to put the kitchens in direct contact with farm cooperatives.

So far, the family kitchens have provided a vital survival tactic for some of Lima's most neglected inhabitants, a guide to tapping reserves of creative community building.

© 1984 The Glove and Mail. All rights reserved